As a superhero-obsessed eleven-year-old, I had a head start on the Batmania that swept the country when director Tim Burton’s Batman hit theaters in June of 1989, almost 30 years ago. I already read the junior novelization, I bought the Toy Biz action figures, and I wore way too much tie-in clothing (including a pair of boxer shorts my dad dubbed “Buttmans”).

To me, Batmania was a naturally occurring phenomenon. After all, Batman was the best: of course everyone wants to see him in a movie! And although I had read enough fan letters and newspaper editorials to know that some people were dubious about Michael Keaton in the title role, Beetlejuice was the greatest movie ten-year-old me had ever seen, so why shouldn’t he be the star?

Because first-run movies were too expensive for my family, I didn’t see Batman until it was released on VHS in November. Clad in Batman footie pajamas and swinging my toy crusader by his plastic retractable utility belt, I shrieked with glee when my hero dangled a crook off a ledge and growled, “I’m Batman.” It was exactly what I imagined when I read the comics, exactly what I saw when I animated the panels in my mind, and now everyone else could see it, too.

But after that opening bit, Batman mostly disappears… and instead, the movie focuses on reporters and gangsters and their girlfriends?And it’s kinda more about the Joker? And when Batman does show up, he kills a bunch of people in an explosion? And his muscles aren’t even real?

By the time we get that awesome final shot of the Bat-Signal glowing against a dark and stormy sky, eleven-year-old me had to face the facts: this was not my Batman.

Batman made over $251 million at the box office that year, breaking records at the time, so obviously a lot of people disagreed with me. For them, Keaton was Batman and he always killed people and had plastic muscles, while Jack Nicholson was always the Joker and was always more interesting than Batman.

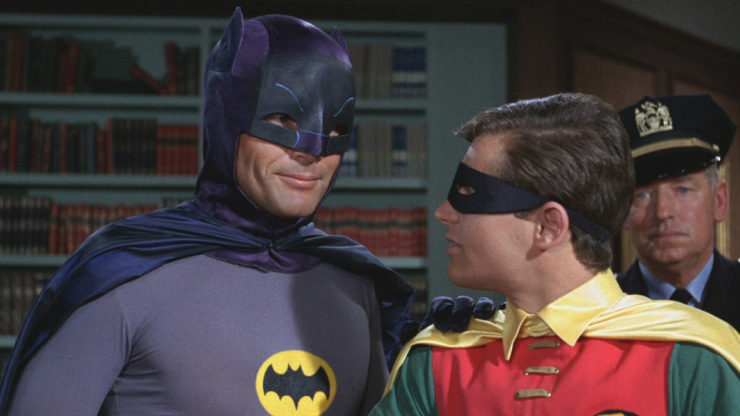

Other people did agree with me that Keaton wasn’t Batman—but they said Adam West was the real Batman, and I hated him! They wanted a Batman who wasn’t serious, the guy who danced the Batusi and made giant “pow” effects when he punched people. The Batman of 1989 wasn’t their Batman because they loved the Batman of 1968, but neither of those were my Batman because that wasn’t the Batman I loved from the comics.

Throughout my life, I’ve seen people complain about various incarnations of Batman in a similar way. The Michael Keaton Batman is the real Batman, because Val Kilmer and George Clooney were too silly. Kevin Conroy of Batman: The Animated Series is the real Batman, because Christian Bale’s angry voice doesn’t scare anybody. The version in the animated series is too cartoony to be the real Batman; Ben Affleck is too old and bored to be the real Batman; Tom King is too pretentious to write a good Batman; and on and on it goes.

These types of complaints aren’t unique to portrayals of Batman alone, of course. When Christopher Nolan cast Heath Ledger, the pretty boy from Cassanova and 10 Things I Hate About You, message boards across the web exploded. “Mark Hamill is the only Joker,” they declared, or asked with anger, “Why does this teen idol think he can compete with Nicholson?”

As strange as it seems in hindsight to question a casting choice that’s pretty universally praised now, these complaints do make sense. As argued in Roland Barthes’s landmark essay “The Death of the Author,” any written work requires a certain amount of co-creation on the part of the reader, who performs an act of writing while reading to fill in the gaps inherent in every work. In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud applied that idea to the literal gaps in a comic book: the gutters between panels. Readers pull from revisions of their own experiences and beliefs and expectations to finish the work started by authors.

We readers invent for ourselves what happens between any explicit information provided by authors, so its no surprise that we feel a certain degree of ownership in these characters. Authors may give characters words and actions, but readers give them a voice and emotions.

Buy the Book

The Survival of Molly Southborne

But here’s the rub: because each reader fills those gaps with material from their own experiences, beliefs, and desires, then each individual reader will necessarily have a different take than any other reader. Keaton wasn’t my Batman, but my Batman wasn’t anyone else’s Batman, either. It wasn’t really even director Tim Burton’s Batman, as he had to make compromises with producers Jon Peters and Peter Guber and didn’t truly get to realize his vision of the character until the sequel, Batman Returns.

So if everyone has their own personal version of characters, how can we talk about them together? More directly, how can we celebrate them when they jump to new media?

Before I answer that, I need to point out the obvious: we know that we can celebrate them together, even when translated through different lenses of popular culture, because we do it all the time. Nerd culture, especially comic book culture, currently rules the popular landscape in a way that surpasses even the Batmania of 1989. My parents, who once patiently and lovingly endured me reciting for them the plots of ’90s comic crossovers, now ask with genuine concern if Drax and Ant-Man make it through Infinity War and Endgame unharmed. As my wife and children sit down to dinner, we watch the CW superhero shows together and discuss the adventures of heretofore unknowns like XS and Wild Dog.

But none of that would be possible if I insisted that XS was the granddaughter of Barry Allen or that Drax was a Hulk knockoff with a tiny purple cape, like they are in the comics I grew up reading. To share these characters with people who haven’t been reading about them since the ’80s, I can’t insist that they’re mine. I need to remember another lesson I learned as a child: it’s good to share.

Granted, sometimes sharing isn’t so fun, especially if I don’t like what other people do with characters I love. To me, Batman’s refusal to kill is just as central to the character as his pointy ears, but neither Tim Burton nor Zack Snyder shared that conviction when they made blockbuster movies about him. I strongly prefer the haunted, noble Mon-El from the Legion of Super-Heroes comics to the self-centered bro who showed up in the CW Supergirl show. And I find Thanos’s comic book infatuation with the personification of death a far more plausible motivation for wiping out half the universe than I do the movie version’s concern for sustainable resources.

But when I read Infinity Gauntlet #1 in 1991 and watched Thanos snap away half of all the galaxy’s life, I sat alone in my room and despaired. I tried to tell my sports-loving brother and my long-suffering parents about what I had just read, but they didn’t care. I was a homeschooled kid in the days before the internet, and so I experienced this amazing, soul-shattering moment all by myself. Sure, no one contradicted my favorite version of the story—but nobody enjoyed it with me, either.

Now, everyone knows about the Thanos snap. They all have their own experiences of horror when Hulk smashes into Doctor Strange’s sanctum to warn of Thanos’s arrival or profound sadness when Spider-man disintegrates. Who cares if those reactions differ from the ones I had when I saw Silver Surfer crash through Strange’s ceiling, or of Spider-man discovering that his wife Mary Jane had died, as it was in the comics of my youth? Now, I can share that experience with everyone.

That’s especially true of revisions to characters that makes them real for different audiences. As a straight white American male, I see myself in a plethora of heroes, from Superman to D-Man. But by making Ms. Marvel Pakistani-American, Spider-man Afro-Latinx, and Dreamer a trans woman, writers have opened the tent of nerdom to people who have finally been properly included, inviting more and more people to celebrate and to create and to imagine together, further enriching the genre.

For this to happen, the characters and the stories have to change. I can’t clutch my favorite versions of Guy Gardner or Multiple Man because those versions don’t belong to anyone else, not even to the people who wrote the comics that made me love the characters in the first place. And worse, I can’t share them with anyone else because my version can only ever be mine. That’s a lonely place, believe me.

I write this the weekend after Warner Bros. announced that Robert Pattinson may play Batman in the upcoming Matt Reeves-directed film. Unsurprisingly but sadly, people are complaining, launching a petition to get the “sparkly vampire movies” guy removed from the film. “That’s not my Batman,” they insist.

And, again, I get it. He probably won’t be my Batman either, just like Michael Keaton wasn’t my Batman way back in 1989. But no Batman is my Batman, nor will it either be their Batman. But…if we can get over that, if we can accept that any act of collective storytelling involves a bit of disappointment balanced out by a lot of communal world-building, then we can see how much fun it is to enjoy these characters together.

In 1989, eleven-year-old me didn’t want a Batman who kills and has plastic muscles. And I still don’t. But eleven-year-old me learned that it’s way better for lots of people to see that Batman is cool, a character we can all be excited about in different ways—and far less lonely than insisting that my version is the right one.

Joe George‘s writing has appeared at Think Christian, FilmInquiry, and is collected at joewriteswords.com. He hosts the web series Renewed Mind Movie Talk and tweets nonsense from @jageorgeii.

Well said.

I for one have always been fine with Val Kilmer’s take in Batman Forever. An acceptable back-up to Keaton’s unexpectedly pretty good take on the character!

I’ve never seen a definitive Batman or, well, any superhero. Each seems to offer one universe wherein that character exists, even the ones that were terrible (looking at you, Batman and Robin).

Loved this :) I’m not particularly invested in Batman (being pretty much solely a moviegoer when it comes to comics. And, scandalously enough, the first Batman movie I was actually old enough to see/enjoy was Batman Forever, which isn’t, from what I understand, a *real* Batman movie).

But I have a few other fandoms I’m more invested of, so I know the pain in seeing it turn into something that’s not ‘yours, or adapted ‘wrong’. And you know…I still think some of those choices were ‘wrong’ and a disservice but at the same time I try and at least enjoy that we have such a great bounty of things to enjoy. My versions still exist, which in a way takes the pressure off all the other versions to be ‘perfect’. It doesn’t mean I will enjoy every single one, but I try not to lose sleep over it :)

Also, as an aside, we just watched Beetlejuice this weekend, as I figured my 8 year old was old enough to be introduced to it. Still one of the all time greats :) (Also, as another aside, Lego Movie 2 actually riffs on this whole idea of ‘the real Batman’ quite humorously in one of its musical numbers. And references Beetlejuice. FWIW I feel like Lego Batman is just as real a Batman as any other incarnation, at least in our household.).

i’ve been ok with most batmans, even the Adam West looking back is quite amusing, but Ben Affleck I always found boring, now with talks of Robert Pattinson , i’m not crazy about him either

Most movie Batmans for me go from okay to great. Adam West sucks as a “serious” Batman, but if you grew up watching the lame Super Friends show, he’s not far off from that iteration so he doesn’t seem to me like his is not a valid take on the character.

My favorite movie Batman so far, for all the flak he’s gotten, is Ben Affleck. Too bad the scripts are garbage, and he ends up acting like a moron or just taking up space while the others do their thing in a brawl. I have to say, though, that I loved every second of the scene where he rescues Martha Kent in “BvS: DoJ.” It was the only time I’ve seen the real Batman from the comics in action beating up bad guys left and right.

The only movie Batman I just loathe is George Clooney. To say he was miscast is an understatement, and to say he then went on to play the character in basically the worst way possible, is charitable. He’s a pretty good actor, but an abyssmal Batman.

For all that the “Twilight” franchise sucks, the kid who plays the sparkly vampire isn’t a bad actor. I’ve no interest in seeing any of those movies, and I read a part of the first novel way back when it came out, thinking it a vampire novel, before the mass hysteria broke out, and ended up putting it down and walking away because it was so bad. However, I’ve seen him in a few indie movies and he’s not bad. Maybe with a good script and director, he can pull a Heath Ledger and surprise us all. I’m not expecting he will, but I’m pretty sure that if the new Batman movie sucks it won’t be because the guy from “Twilight” was in it.

One can imagine that after Richard Burbage retired that theatergoers at the Globe began saying of his replacements, “Not my Hamlet,” “Not my Lear,” etc.

I think Ms Marvel is Pakistani American and not Arab American, but I may be wrong.

What a great piece!

It is so easy to react to things on the internet, and reactions on the internet tend to extremes, anything but nuance.

But everyone has a right to love or hate whatever they want, and fiction is always, always subjective.

It is all too easy to feel and insist that one’s own opinion is the most correct and valid, even with other people that we know and care about. Fandom is all too often made into a kind of tribalism, where you are either part of it and correct, or not.

As the article said, it is much more fun to enjoy others’ enthusiasm.

What was it TLJ said, better to save what you love than destroy what you hate.

Any time a take on a particular character doesn’t resonate with me, I look at it from a Multiversal perspective. For example, I may not like the Adam West Batman, but plenty of other people do, and that’s great. It means that they prefer a Batman from a brighter, sillier universe while I prefer a Batman from darker, more dangerous universes such as the ones portrayed in the Nolan films and BTAS. I think there’s more than enough room for multiple takes on any given character (or franchise).

@8 I like that!

@8 my idea too, dark-gothic atmospheres work better

I don’t have a Batman. I haven’t enjoyed any of the Batman movies very much, and I’ve never read a single comic. And now I’m not sure why I’m even commenting. I’ll stop now.

@11, well the article could refer to any adaptation of any fandom. It is not limited solely to Batman.

The 1966 Batman was my first Batman (I was 4) and no one now can really understand how big a deal it was. They showed new episodes twice a week (can you imagine GOT doing that?). It had tie-ins galore, long before the GI Joe, He-Man, etc., cartoons were made to sell toys. And, in the Adam West movie it had the first team-up, of villains(!), that I know of. Frank Gorshin will always be the Riddler!

Adam West is my Batman, fight me old chum!

@@.-@

What, you mean die before the movie is released and thus ensure nobody dares say anything bad about his performance for a decade or so? Pretty dark man, pretty dark.

@Ryamono: You’re absolutely correct. Thank you for pointing that out — I’ll see if I can get it changed. Thanks again!

@6, 15 — Fixed, thanks!

I try not to judge actors before I see them in a role. Pattinson is by all accounts a talented actor and could bring a lot to the role I’m sure.

I do miss how much physicality Bale brought to the role even if I disliked his batman voice.

I was surprised how much I liked Affleck as grizzled, old, failure Batman. I wish we got to see more of that, but he was handicapped by awful scripts and bad plans for a franchise.

In a comments section of a forum that has absolutely nothing to do with geekdom, some guy was talking about all the iterations of all the various superhero franchises he’s seen, and he’s never been remotely happy about any of them. How sad is that.

There’s a place for compartmentalization: I liked the Mon-El character on Supergirl fine for what he was, but he wasn’t, you know, Mon-El. And that’s okay, Mostly.

(The show’s penchant for using the name of one DC character and the background another has become something of a running joke– e.g, the villain with Vartox’s name and the Persuader’s shtick in the pilot– though I don’t think there’s a specific DC “royal heir who Learns Better” character that TV Mon-El maps to.)

And I remember the violent reaction against “Mr. Mom” playing Batman, which were wrongheaded regardless of how one liked the final product. A generation still in the throes of reaction against the Adam West Batman and convinced that Frank Miller was the one right way to handle the character were expecting and fearing broad comedy, and certainly didn’t get that. (From Keaton, at least.) The anti-Pattinson reaction is likewise at least premature, and likely equally misdirected. (DC’s uneven recent record means the film may still misfire, but not based on casting alone.)

That said, I think there’s room to mourn elements that define a character to a given audience. Sometimes the creators and new enthusiasts really do leave some fans behind in their pursuit of the new thing. That’s probably unavoidable, and not necessarily bad. But likewise the recognition that the character bearing a certain name or costume no longer reflects the primary thing you were once a fan of is a thing that happens, and is felt as a loss. (Even if it’s someone else’s gain.)

And there’s ground between “Only [specific creator’s] version is valid– except for their last few years when they totally went off the rails. And the first few years when they hadn’t gotten the feel for it yet. And the Annual.” and “Well, sure, the costume, personality, physical appearance, powers, and secret identity are all different, and in some cases antithetical, but it’s basically the same character anyway.”

Ditto changes that make the character less distinct and more like the current flavor of the month, which can seem downright wasteful.

(E.g., turning Aragorn into a Hollywood Reluctant Hero worked in the context of the story Peter Jackson wanted to tell. That story works in its own context. But there are just an awful lot of reluctant heroes initially resisting their destiny in adventure films, and not a lot of characters like Tolkien’s Aragorn.)

None of which, of course, justifies making an effort to ruin the fun of the fans of the new incarnation of the character. But there’s certainly a genuine sense of joy or relief to be felt when a new revival or adaptation shows signs of Getting It. (Whatever It may be.) Especially after a few years or decades of missteps.

The DC Multiverse canonically includes 52 different “Earths” (more if you account for Hypertime), so it’s trivially easy to write every interpretation off as being from “some other universe” (and equally easy to justify building your own personal continuity). I’ve come to terms with treating official canon, whether DC, Marvel, Transformers, or Star Wars, as a sort of buffet from which I can draw ideas from wherever I like; the CW Flash with a DCEU-based Wonder Woman teaming up with Green Lantern from his animated series? It’s all good.

(And “my” Batman is based on the version David Mazouz played on Gotham.)

@14: Ha! I was shooting for “not completely suck in contrast to what everybody expected.” For all that Adam West isn’t my fave, I have to say that Christian Bale dancing the Batusi would have actually improved “Dark Knight Rises.”

There are well cast stories, there are poorly cast stories. An alternative reaction to being outraged is to ignore it.

Also keep in mind “bad casting” often equals = casting not targeted to your tastes. Their is a lot going on in the Superhero genre where they are targetting a specific audience – e.g. older teenagers, women, horror fans etc…and a lot of the time marketing makes it pretty obvious which group they are targetting (e.g. the recent batwoman trailer makes it pretty obvious who that show is intended for)

It might not be you.

For background, I started reading comics in between the Golden and Silver ages. I’d been reading stories about Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Aquaman and The Blackhawks (my personal favorites, at least until they got those stupid multi-colored uniforms) for years before DC changed the universe with The Flash in Showcase #4 (slightly predated by The Martian Manhunter, who doesn’t count for some strange reason). So my view of these characters is informed by decades of reading comics. I stopped some time after the end of the Bronze Age, I’d guess circa 1990, by which time I was reading almost exclusively French comics (Métal hurlant) and UK comics (2000AD, speaking of which, Karl Urban was my Judge Dredd, shame there will be no sequels or a series) and a few offbeat US titles like Those Annoying Post Brothers & Flaming Carrot. Christopher Reeve is pretty much my Superman. One of Supe’s superpowers is super mental health, as explained by Bill to The Bride at the end of Kill Bill 2, and Reeve nailed it. The movie wasn’t perfect. I didn’t like the ending. But Reeve was. He was a bit less so in the sequels. A Superman who had regained his powers simply would not have beaten up a bunch of bullies who had tormented him when he was powerless, as he did in Superman II. Gal Gadot is pretty much my Wonder Woman. The movie wasn’t perfect. I didn’t like the ending of that, either. But Gadot perfectly embodied the pacifist warrior that I felt WW should be. I have yet to see my Batman. Adam West, Michael Keaton, Val Kilmer & George Clooney certainly weren’t it. Bale’s performance was OK, at least in the first 2 Nolan movies. I loathe The Dark Knight Rises. Surprisingly, Affleck came closest as an aging, bitter Batman (something that I could see happening to Batman, but not to Superman or Wonder Woman). This despite my serious issues with him killing and the fact that I am NOT normally a fan of Ben Affleck. He was certainly better than Henry Cavill’s dire, morose Superman. Batman the Animated Series and Batman Beyond were decent, but I’d still like to see someone nail the role in a live action movie. I don’t hold out much hope for Robert Pattinson. I never saw the Twilight movies, so I don’t hold that against him, and I thought he did fine work for David Cronenberg in Cosmopolis (although the movie was definitely minor Cronenberg) and the much better Maps to the Stars. But I don’t see him as having the requisite physicality. Sure, the suit can be beefed up, as it was for everyone else, but his face is too thin. I’m concerned that the mask will overpower his face. We’ll see. I won’t entirely write off the idea.

Movie Batman in particular can be tough as you’re really casting two very distinct roles in terrifying vigilante genius Batman, and rich heir/businessman/philanthropist with some amount of conscience (but not too much) Bruce Wayne.

While I dislike Tim Burton’s take on the character being okay with killing, I think Keaton actually did a really good job as Batman in the role. But he was a terrible Bruce Wayne.

In the (awful) Schumacher films, I thought Kilmer was all around bland in both roles, with a passable Bruce Wayne. I thought Clooney was actually a really good Bruce Wayne, but hated his Batman.

I like Bale’s take on both, and felt similarly about Affleck’s too. They both did a good job portraying a different public face, secret life and how that meets internally. Even through Dark Knight Rises and the DCEU movies making them do things that felt stupid and out-of-character.

I’m cautiously optimistic about Pattinson.

Too many comic books series have suddenly done an about-face with their characters, and if I screamed “THAT’S NOT MY ___,” every time, I’d have nothing left to enjoy. That’s the nature of the beast. As long as they tell a good story, I accept the paradigm shift. (Or just call it one story in a slew of multiverses.) I’m just happy–speaking as someone who is outside the straight-white-maledom of comic/nerd culture–that superheroes are out in the mainstream and being able to share my excitement with everyone.

I haven’t even read this, yet, but I have to say that the only Batman who has ever really done it for me is the comic book character, and/or the cartoon character. Apparently, none of the “human” versions can live up to that well-drawn fantasy. Which is really strange, because I always liked Batman best because he was human, and relied on his brain and his tools instead of superpowers. No accounting for taste. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with those of you who have different preferences, it’s just that none of the actors has ever come close to that guy in my head.

Well said – I have never seen “my” Batman – someone in spandex (not clumsy armor) who is a brilliant detective, a superb martial artist and aerialist, a man who will never quit, no matter what happens. That’s why I loathed Nolan’s version of Batman, and why I thought there was hope for Ben Affleck’s take… But, like Superman (Henry Cavill), his portrayal was marred by both the writing and directing… As for Superman, Cavill is wonderful but hasn’t been able to surpass Christopher Reeve in his portrayal. Again, this is because Snyder and the writers decided Superman needed to be darker… When will they get that Batman is the night and Superman is the sun? They complement one another, and, in the best worlds (World’s Finest in the Silver Age) they are friends and colleagues who respect one another. Thankfully, Matt Reeves wants to showcase his Batman as a brilliant detective – finally! As with all these movies, I wait until I’ve seen them before I complain… To that end, Green Lantern was a terrible disappointment – bad choices and terrible writing – oh, what could have been!

Thanos is so not scary in Infinity War and Endgame because he has a somewhat “believable” motivation behind his acts of evil. Thanos in the comics is horrifying because he is purely nihilistic- obsessed with death – his motivation for the snap doesn’t come from a misplaced notion of him saving the universe from suffering. Thanos is just an evil dude. You’re incapable of rationalizing his motivation. In many ways, the Thanos of the comics is akin to The Joker in Nolan’s The Dark Knight. Heath Ledger’s Joker was shocking and horrifying because he came out of nowhere as an agent of chaos who literately wanted to watch everything burn and he was the opposite of Batman’s nature. He was pure evil. Pure chaos.

In regards to Batman, I too was quite young when Keaton ruled. And I loved the Batman films at the time and even enjoyed Batman Forever – it’s campy sure but fun (I remember I had the poster in my room!). For me though, I absolutely loved Nolan’s interpretation. It wasn’t campy. It was smart and gritty and amazingly holds up a decade or so later. The Dark Knight in particular is an absolute classic. I fell like Nolan’s movies really felt more like the classic Batman comics such as Year One, The Long Halloween, The Dark Knight Returns but with a 21st century twist. I enjoy the Burton film (mainly for the German Expressionistic aesthetic) but they don’t hold up as well and I agree Batman shouldn’t kill! That’s one of my favorite aspects about him!

@28

Agreed. Not only that, but Batman hands the people he captures over to the police, so they can have due process with lawyers and jury trials and publicly overseen judicial verdicts. That is what makes Batman a good hero. Which is why I get so annoyed by the “Batman should kill the Joker” fanbois, because Batman is not about taking the place of the system but of making the system work. I know, the first 18 months argument, but for the major chunk of his existence that is Batman.

It is also why I bailed on the CW shows, especially Supergirl and The Flash. Secret prisons, paramilitary death squads, not public oversight? Hard pass; that is not a Superhero, that is a villain who happens to be the protagonist with no self awareness.

Joe,

I am about 15 years older than you and have gone through the exact same process.

I applaud your outlook and approach to enjoying “your” heroes and sharing them with the world.

–JMc

I have a different take on “This isn’t my xyz!”

I’m more of a fan of writers and artists, than I am of the characters, so I follow writers and artists from one character to another. Creative teams take characters into different directions to try and tell a story. Sometimes they cover an existing story in a different way, which changes the historical narrative for that character. Such as John Bryne not having Jonathan Kent die, since he was of the opinion that if Clark was raised right, then he wouldn’t need the death of his father to spur him on to do right. People hated that! Walt Simonson wrote Odin out of the Thor comics as he felt that Odin was too much of a Deus ex machina to stay in the comic. Yet Odin was brought back shortly after Walt left the writing of Thor.

So I take the same point of view with movies and TV shows. Well, I don’t accept the TV version of Jon Sable! Anyway, I see each one is a creative take on a character or group. I don’t get as upset by casting choices as much as I do with inept story telling. So, going back to Thor, wouldn’t it have been a far more epic conclusion to Ragnarok to have a giant Anthony Hopkins in battle armor fighting Surtur? Where Odin falling into the chasm while grappling with Surtur would be more climatic in saving Asgard, than just walking off into a field and vanishing? The sword could still be left behind and explode and destroy Asgard if the writers really had to take that story direction, or maybe it could just make Asgard unlivable which would still force the evacuation?

I don’t understand why people hate when something that is taken out of context, ie a picture of Brie Larson in her Captain Marvel costume while she’s eating lunch while on location, and go off the hinges complaining! Based on not being a big Ben Affleck fan I wasn’t too sure about Aflect being Batman(especially when considering Daredevil), but I didn’t hate the idea. I thought he was great! I couldn’t wait for an Afflect Batman movie! So Robert Patterson might very well be the best portrayal of Batman that we’ve ever seen, but it might also be the worst script we’ve ever endured. Let’s just wait and see.

Robert Pattinson is actually a good actor when he doesn’t utterly despise the character he’s playing (seriously, he *loathes* Edward Cullen), so I don’t have any worries with him being cast as Batman.

I worry about the fact that the majority of the problems with DC movies come from the scriptwriters, directors, and producers.

Adam West’s Batman is overly silly to the point where you keep expecting a member of Monty Python to show up dressed as a 1970s British military officer and order production halted because it’s TOO silly, but his portrayal was pretty much perfect for how Batman was in that time period.

Michael Keaton’s Batman is the way Batman was when it was made. A grim, gritty, “DING DONG THE COMICS CODE AUTHORITY IS DEAD!” rejection of the campy silliness of the Silver Age (The Killing Joke was published the year before the movie came out).

Val Kilmer’s Batman is basically a forgettable focus of a schizophrenic mess of a movie that tried to staple the grimdark of the newer Batman to the silliness of the old. He does an okay job, but doesn’t stand out next to the massive overacting of Jim Carrey and Tommy Lee Jones.

George Clooney… The best I can say about him is that he manages to not be the worst part of his movie, which continues the trend of Batman Forever and manages to make it worse.

Christian Bale manages to ‘get’ the separation between Bruce Wayne, Bruce Wayne’s Public Smarm, and BATMAN, but his version is heavily leaning on the problematically-grimdark storylines from Frank Miller (who still at least remembered that Batman refuses to kill).

From what I’ve heard, Ben Affleck does an okay job with the role, but his Batman is forced to kill largely just because the people running DC’s movies are wannabe-edgelords who think that Batman and Superman, the two biggest examples of characters who refuse to kill, HAVE to be GRIMDARK!!!!! to be popular.

@31

I take the view that it matters not a whit that Pattinson is a good actor or not, he was still in Twilight.

@33 – “It doesn’t matter if INSERT ACTOR is good, they were in REVILED MOVIE” seems like a bit of a slippery slope.

Pardon my flagrant hyperbole here, but that’s like saying “Sean Connery was in Zardoz and Highlander 2, therefore the entire rest of his career doesn’t count”. Or, more to the point, given what just came out, it would be like saying “I’m not going to watch Good Omens because Michael Sheen was in Twilight!”

My thoughts are that an actor should not be judged for taking a role, especially an extremely lucrative one early in their career, just because the movie is execrable.

Shit. I forgot Sheen was in Twiglet. Well, good job I already watched GO because I won’t be rewatching it now. I won’t be watching anymore movies Connery makes after that horrible League of Extraordinary Gentlemen movie he did either. Some movies are so bad they deservedly kill the careers of everybody in it.

@35 – That’s pretty much exactly the same as people who scream “RUINED FOREVER” whenever a franchise makes a minor change, and I have never understood that mindset. Any decently-prolific actor or actress *will* end up with at least one that’s worthy of MST3K or Rifftrax, and if you refuse to watch the work of anyone who’s ever been in something bad, you’re going to deprive yourself of enjoying a lot of actually good movies.

I’ve seen the Rifftraxes of all of the Twilight movies, and Michael Sheen’s performance in them was the most hilarious thing in that experience that wasn’t provided by Mike Nelson, Kevin Murphy, or Bill Corbett. He went the Jack Palance route of “this movie sucks, I’m just going to have the most fun with my screentime that I can”, and it worked.

When asked if he had seen Jaws 3D: The Revenge, lead actor Michael Caine said that he hadn’t, but he had seen the house the paycheck paid for.

Actors have to eat and pay the bills like anyone else. The Twilight movies shouldn’t be held against the actors in them, as long as the actors didn’t do a bad job. It’s best – for everyone – simply to let some things be forgotten.

Was there anyone, anyone at all, who was offended by the different versions of Spiderman in Into the Spiderverse? I thought that was a great example of how a character can be interpreted in radically different ways, as long as the most important aspects of the character remain invariant. The Noir Spiderman, the porcine Spiderman, the Japanese little-girl-inside-a-robot, even Gwen Stacy as Spiderman. Their outsides differed, but they all had the same heart. (Metaphorically speaking.) And that was the point. Peter Parker may die, but Spiderman goes on. He’s an idea, not any particular person.